Strategies for Maintaining Civility

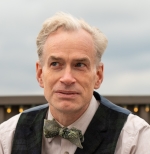

By Chad Snyder

Bad behavior is not new to the legal profession. Nearly 40 years ago, Judge Richard Curry wrote in the Illinois Bar Journal, that “‘zealous advocacy’ is the buzzword which serves to legitimize the most outrageous conduct, conduct which regrettably debases the profession as well as the perpetrator.” He could have written the same words last week.

There is nothing wrong with zeal. But being zealous does not mean you need to be a zealot. Or a jerk. Zeal need not be, and should not be, “a weapon to use to club opponents.”1 In this article—adapted from my “Don’t Be a Jerk” CLE—I’ll briefly touch on two aspects of this persisting problem. First, I'll name some reasons lawyers might resort to jerkish behavior. And second, I'll share a few tips on how to keep from indulging in that behavior ourselves.

Some Causes of Jerkitude

The perception that it is what clients want

In many cases, it may actually be what the client wants. That does not make it appropriate. As the comments to Rule 3.2 confirm, we should advocate for the legitimate interests of our client; demeaning or abusing the other side is not a legitimate interest. Acting like a jerk might even cost you—or your client—money. In affirming a trial court’s substantial reduction of a prevailing plaintiff’s attorneys fee award, the California Court of Appeals observed that the lower court “correctly noted the incivility in Karton's briefing. Attorney skill is a traditional touchstone for deciding whether to adjust a lodestar. Civility is an aspect of skill.” Karton v. Ari Design & Constr., Inc., 61 Cal. App. 5th 734, 747(2021) (emphasis mine).

The belief that this is just how law is practiced

This may be gleaned from too much TV. But it more likely comes from unfortunate experiences with lawyer-jerks in early years of practice. Jerks tend to create more jerks. It would be better to learn and remember anarchist Emma Goldman’s admonition that, “Lack of fairness to an opponent is essentially a sign of weakness.”

The belief that an aggressive attorney is more impressive.

As the old saying goes, “If you don’t have the facts, argue the law. If you don’t have the law, argue the facts. If you don’t have either, pound the table.” Some lawyers seem to just jump to table-pounding on the theory that it gets the judge’s attention, maybe impresses them with the lawyer’s commitment and passion.

Judges do notice. They are not impressed. Encountering such lawyers as a mediator, I haven't been impressed either—at least not favorably. Credibility is our currency, and jerkish, aggressive behavior weakens that credibility. The louder a lawyer yells or pounds the table, the more they rely on insulting or demeaning the other side, the less likely a judge, mediator, or opposing party is to believe or trust them. “Judges like bullies and jerks no more than the average person,” Hennepin County Judge Jay Quam wrote in an excellent 2011 Bench & Bar article.2 Judges don’t trust jerks and bullies, he wrote, and “if the judge does not trust a lawyer, the judge will not rely on what the lawyer says.”

Fear

Fear is a powerful motivator that can, without us even realizing it, override not just our better nature, but our reason. If we’re afraid we will be seen as weak, we lash out. If we are afraid that we don’t know everything we need to know, we cover it with bluster and anger. To some extent, we can avoid this pitfall by following Rule 1.1 on competence; if we know our cases, we are less likely to let fear get hold of us.

Sometimes it works

The unfortunate truth is that sometimes bad behavior gets results, at least in short-term or one-off situations. But in law we are almost never in one-off encounters. Cases last months. We may have another case with opposing counsel down the road. That judge will probably be your judge in another case someday. Being cooperative and civil now brings benefits over time for our current client and for future clients. As Judge Paul Friedman, a federal judge in D.C., phrased it, “lawyers offer to the clients their own professional reputations and the integrity and credibility with the courts that they have established over time.” The legal community isn’t that big. If a lawyer is rude or obstructionist or dishonest, word will get around and people won’t extend their trust, good faith or the benefit of the doubt to a known jerk.

“They started it!”

This may be the most well-worn path to jerkish behavior. It is easy and human to respond to an insult (real or perceived) with an insult. But “they were a jerk to me first!” is not persuasive. It didn’t work when you pulled your brother’s hair, and it really doesn’t fly for adult professionals. As a New York judge put it, “In the realm of professional conduct, provocation is, at most, a mitigating circumstance and not a complete defense to wrongful conduct; the same is true under the Federal Sentencing Guidelines … and the rules of the fifth-grade classroom.” Alexander Interactive Inc. v. Adorama, Inc., 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 113343 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 14, 2014).

Ways to Avoid Being a Jerk

It sounds easy—just don’t be a jerk. But we don’t always see the ways we are crossing lines, in part because some of what we do is ingrained in the legal culture or has become so much a habit that we don’t think about it. What is offered below is a far-from-exhaustive list of suggestions to break out of habits.

Plan your case from the beginning.

Competence is an ethical requirement. It also helps reduce the stress that might spark bad behavior. If you start your case by understanding the controlling law, you will have a better understanding of your best (and weakest) arguments, the evidence you have and the evidence you need, and the likely outcomes and remedies available to your client. That planning sets you up to be forthright and confident—and more trusted—in your dealings with the opposing party and the court.

Do discovery better.

Discovery is a jerk’s natural habitat. Volumes can be written on how it spirals into depths of jerkitude. Here are just a few ideas that might pull you out of that nosedive.

Draft discovery targeted at the facts of each case, rather than relying on boilerplate. Requests that are clear, concise, and understandable tend to get better answers and are harder to object to.

Make focused objections. Remember you don’t have to object to every request; if you don’t have a valid objection, don’t object. When you do object, have a reason and connect the reason to the request. If you are cutting and pasting objections, there’s probably a problem. Focused objections minimize discovery battles and are more likely to be affirmed if you do end up in motion practice.

Skip “general objections.” They’re irritating and courts uniformly declare them “ineffective,” so why waste time on them? Fredin v. Middlecamp, 2019 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 235684, at *5 (D. Minn. Oct. 25, 2019).

Don’t be hypertechnical. You know what words mean. Give the words in discovery requests their reasonable meaning. If you honestly don’t understand a request, try asking.

Don’t take personal shots.

There is pretty much never a need for lawyers to make litigation personal. Nor is there any value in it. That clever, cutting remark in your e-mail may feel good for a moment, but it isn’t going to advance your client’s cause. No one in the history of arguing has been persuaded to change their mind by being insulted. See, e.g., all of Twitter.

The same rule applies to briefing. Aiming comments in your brief at the opposing lawyer is not persuasive. Don’t call an argument—and by extension the person making it— “disingenuous.” Just address the flaws in the argument.

Before you respond, take a breath.

Then take another breath. Just because you can fire off an angry and self-righteous e-mail doesn’t mean you should. Anger seldom makes us smarter. So before you commit your fury to writing, walk away from your computer. Put down your phone. Scream bad words into a pillow.

It helps to assume everything you say or write to opposing counsel will be read by your judge. Do you want the judge to see you as vindictive, insulting, demeaning, or petty? Of course not. Even if the other side started it, be the lawyer who rose above.

Give the benefit of the doubt.

Maybe the other lawyer didn’t intend a slight. Maybe the badly-written question was the result of bad editing, or a misunderstanding. Many battles can be avoided by simply not assuming the other person had a bad motive.

Pick up the phone.

A conversation can calm a situation or clear up a misunderstanding far faster than a series of e-mails or letters. Don’t do everything in writing because you’re trying to build a record. If you can head off a confrontation, you won’t need a record.

Finally, consider the possibility that you might be wrong.

Hey, it happens.

Chad Snyder is a mediator and litigator at Rubric Legal in Minneapolis, where he helps parties (hopefully civilly) resolve disputes over intellectual property, contracts, and business relationships. A perfectly adequate guitarist, he plays in a garage band you’ve never heard of. He is also pursuing a Masters of Divinity at United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities. Chad tries, with mixed success, to not be a jerk.

NOTES

1. John Conlon, It’s Time To Get Rid of the ‘Z’ Words, Res Gestae February 2001