A profession at the crossroads

By Damien Riehl

Since November 2022, when ChatGPT raised the world’s consciousness of the power of generative AI tools such as large language models (LLMs), the legal profession has debated a particular question: Might LLMs—and the companies that run them—be performing the unauthorized practice of law (UPL)?

In many states, including Minnesota, the UPL statutes prohibit “prepar[ing] legal documents” and giving “legal advice.”1 Central to the UPL debate is the distinction between two concepts: “legal information” and “legal advice.” The caveat is familiar—but does the distinction make sense anymore?

Historically, “legal information” has included primary law (statutes, regulations, case law, administrative opinions) as well as secondary materials (treatises, articles, commentaries on the law). Legal information encompasses abstract legal concepts (such as the elements of a breach of contract claim), as well as the particulars of black-letter law—all as provided by legislators, judges, and regulators.

Legal information is the foundation of our legal system; it must be accessible to all. We’re all bound by the law—so we all must have access to it. As the Supreme Court noted in 2020, “Every citizen is presumed to know the law, and... ‘all should have free access’ to its contents.”2 That access to legal information is provided by various free resources, such as Google Scholar (for cases) and Cornell’s Legal Information Institute (for statutes).

In contrast, “legal advice”—that certain something that only lawyers are authorized to provide—has traditionally been viewed as applying legal information to specific facts. Throughout human history, the only entities that could apply law to specific facts have been humans. But with the advent of LLMs, machines are increasingly capable of applying the law to specific facts (or, if you prefer, applying specific facts to law). As such, we now must confront novel questions about whether LLMs providing “legal information” might also be supplying “legal advice.” Indeed, if you upload a statute into an LLM and ask it to consider how your specific facts apply to that statute, the LLM will provide a response. And that response might be shockingly similar to the words that a lawyer would write. Maybe even better.

Those LLMs are also likely to provide the same types of disclaimers that you provide in offering details about your firm and its practice areas on your website: “This is not legal advice.” Of course, these disclaimers help keep lawyers from creating attorney-client relationships. Do they also keep consumers from believing that any attorney-client relationship exists when those consumers use tools like LLMs?

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder; legal advice is in the eye of the consumer. Would any consumer think that Google or Microsoft, when their tools expressly announce “I am not a lawyer,” is acting as their lawyer?

LLMs’ role in providing legal information

The newfound ability of LLMs to provide more useful legal information potentially challenges traditional notions of “legal advice.” For decades, millions of consumers (and, if we’re being honest, most lawyers) have turned to Google and Google Scholar to answer legal questions. “What are the elements of a breach-of-contract claim in Minnesota?” Has anyone believed that all these years, Google has been providing “legal advice”? Of course not.

Google is often the tool of first resort for lawyers and consumers alike. Unlike lawyers, low-income and middle-class consumers often rely on Google as their only source of legal information. The role of “legal information” is so important—and our help of low-income persons has been so poor—that Google has, for decades, been the primary way that consumers find and interpret legal information.

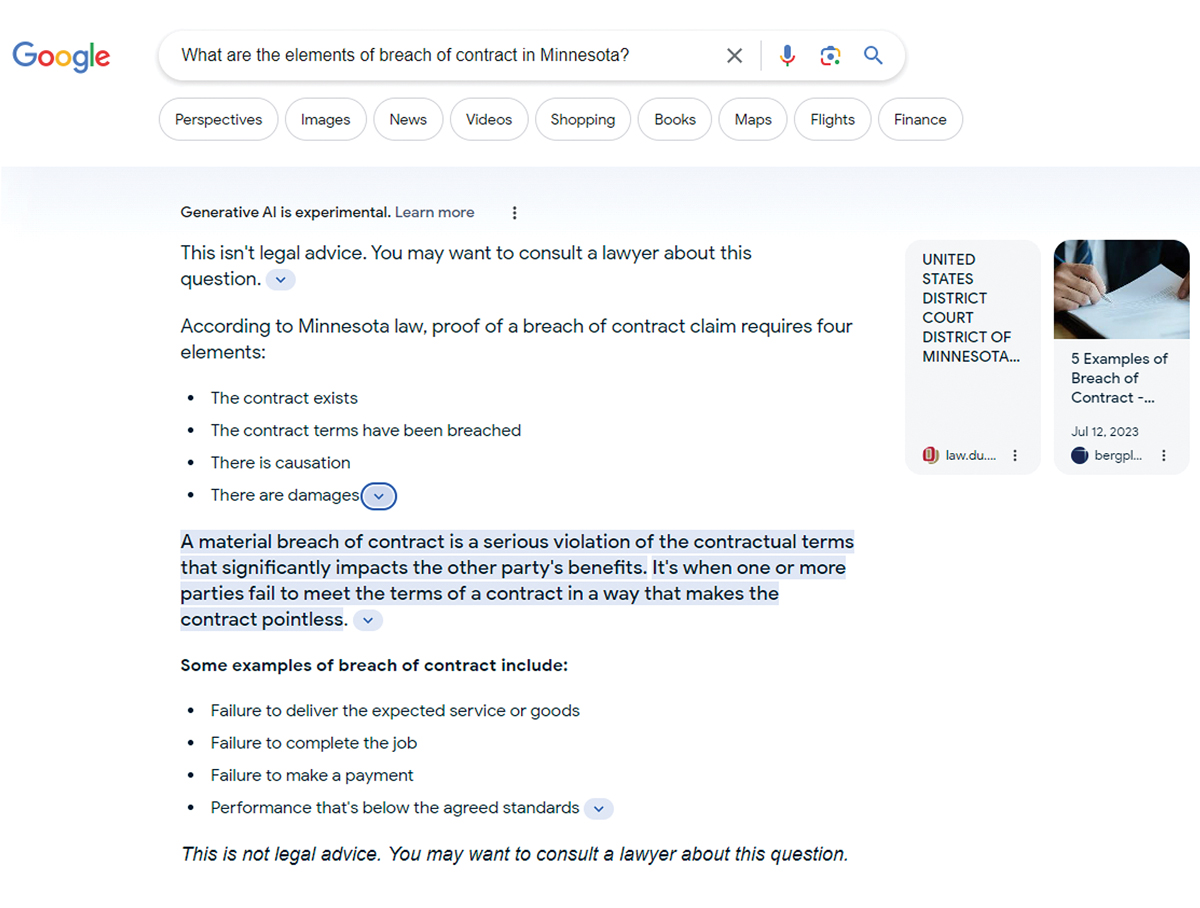

Today, in addition to pointing users to primary law, Google also provides generative AI answers. For example, if you ask Google the question, “What are the elements of breach of contract in Minnesota?” — Google can now provide a narrative answer:

Note Google’s prominent disclaimers: “This isn’t legal advice,” “You may want to consult a lawyer about this question”—on both sides of the answer.

An important question: Given those disclaimers (or even without them), would consumers view Google’s output as legal advice? Or mere legal information? If you were to poll consumers, what percentage do you think would say that Google is acting as their lawyer—performing the unauthorized practice of law? This is almost certainly “legal information.” Especially given Google’s clear disclaimers.

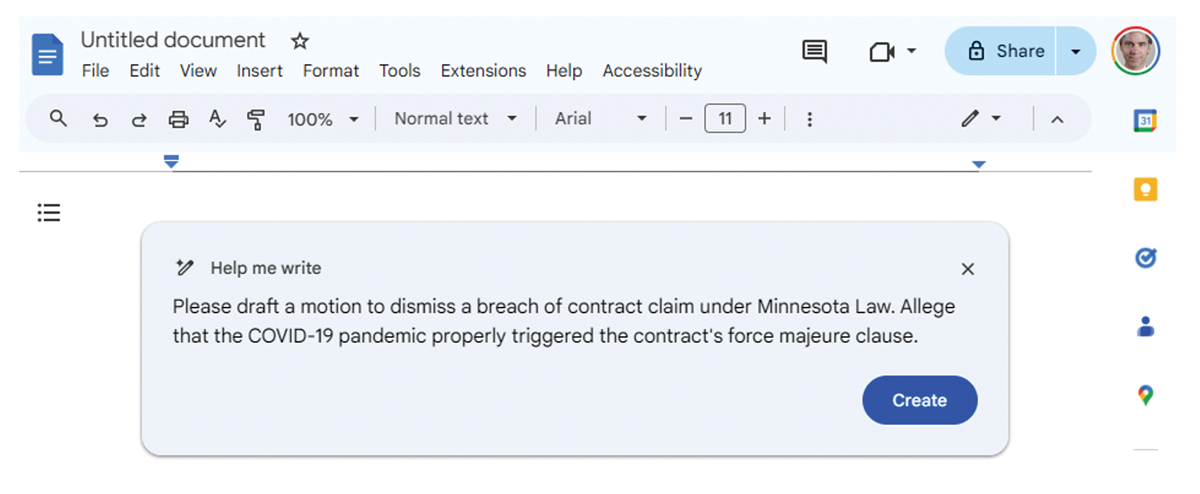

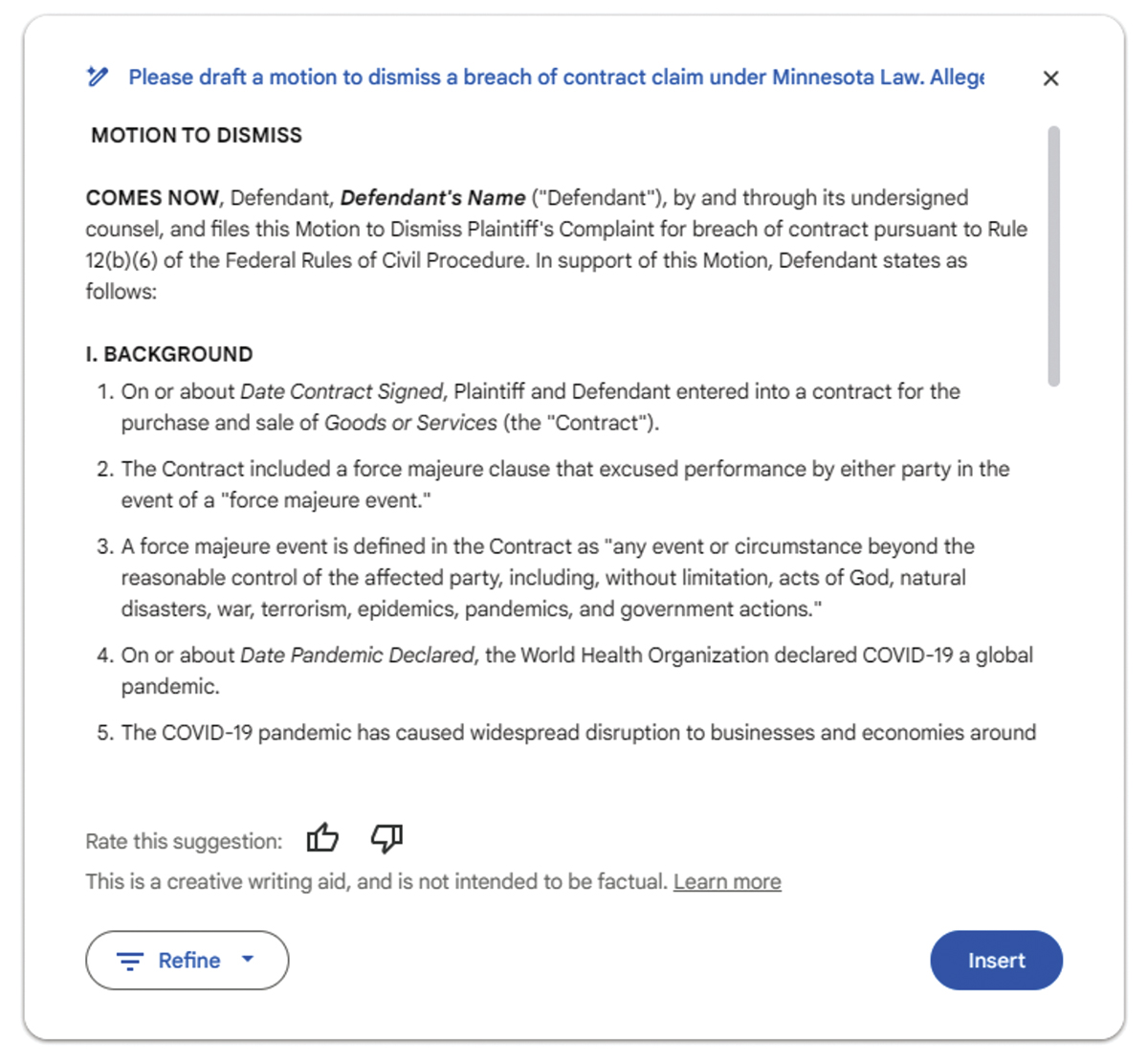

Now let’s go a step further: Consumers ask the same company (e.g., Google) to draft a motion to dismiss using that legal information, applied to specific facts (covid-19, say). Would any consumer consider this “legal advice”—or would they continue thinking that they were just “Googling it”—that is, obtaining legal information?

Here, is Google giving “legal advice”? Is it “prepar[ing] legal documents”? Minn. Stat. §481.02, subds. 1–2 (2023).

If your answer is, “Yes, Google is either providing ‘legal advice,’ ‘prepar[ing] legal documents,’ or both,” what then? Prosecute Google? Keep Google’s service from low-income consumers?

Chief Justice John Roberts, in his 2023 Year-End Report on the Federal Judiciary, provided these words regarding the power of AI to help low-income individuals: “For those who cannot afford a lawyer, AI can help. It drives new, highly accessible tools that provide answers to basic questions, including where to find templates and court forms, how to fill them out, and where to bring them for presentation to the judge—all without leaving home. These tools [AI] have the welcome potential to smooth out any mismatch between available resources and urgent needs in our court system.”3

Those words seem pretty clear: Chief Justice Roberts appears to favor using LLMs to help the low-income population bridge the access-to-justice gap. We should, too.

Imagine the converse: “Sorry, poor people, you don’t get the good tools. Despite Justice Roberts’s words, your reasonable, Google-created motion is prohibited as the unauthorized practice of law, so you’re stuck with ‘plain old Googling’ to draft your more awful motions (that will be more easily dismissed). It’s for your own good!”

Or would it be better to interpret the Google tool’s output, as shown above, as “legal information” and not “legal advice”?

Of course, we are weighing this decision even as lawyers themselves can use LLMs—in products like Westlaw, LexisNexis, and vLex (Fastcase)—to make the practice of law faster and more effective. When a lawyer uses Westlaw or CoCounsel to draft a legal document, is the legal-research company performing the unauthorized practice of law? Of course not. Legal research tools have always been mere “legal information.”

What does this mean for equal justice under the law? Do rich people who can afford lawyers get access to the best LLM-based tools while poor people are stuck with Google search? Access to justice, indeed.

The “legal information” well goes deep. The law consists solely of words. Words are information. And LLMs can now reason with that information, applying facts to law. But that seemingly magical application does not magically convert “legal information” into “legal advice.”

UPL or free speech?

Might all the talk about “unauthorized practice of law” implicate another legal concept, “freedom of speech”? Plaintiffs in two cases, Upsolve and Nutt, have successfully argued that constraints on professional assessments (legal advice and engineering opinions) constitute unconstitutional constraints on free speech.

In Upsolve v. James, the Southern District of New York granted Upsolve a preliminary injunction, using an “as applied” standard to hold that Upsolve’s argument (that New York’s UPL statute unlawfully constrains Upsolve’s ability to provide low-income persons information, thereby constraining Upsolve’s freedom of speech) is likely to succeed on the merits. The case is currently being appealed to the Second Circuit.4

In a similar case from North Carolina, Nutt v. Ritter, a federal court recently held that the North Carolina Board of Examiners for Engineers and Surveyors violated a retired engineer’s free-speech rights. In December, the federal court held that the regulators’ attempt to prohibit the retired engineer from providing an engineering report constituted an unconstitutional violation of free speech. The court reasoned that the engineering guild’s “interests must give way to the nation’s profound national commitment to free speech.”5

Looking to the Nutt case, is “unauthorized practice of engineering” distinguishable from “unauthorized practice of law”? From a public policy perspective, which is more dangerous: bad legal advice or a bridge collapse? Yet the Nutt court still held that the “unauthorized practice of engineering” constrained free speech unconstitutionally. How might Minnesota’s UPL statute, or any state’s, fare under this standard?

These two cases raise similar, difficult questions: Can states continue asserting UPL statutes without impinging on free speech rights? Upsolve is before the Second Circuit, and North Carolina federal courts appeal to the Fourth Circuit. Will they both be upheld on appeal? Or are we looking at a circuit split of the sort that the Supreme Court—led by apparent LLM sympathizer John Roberts—will have to resolve? For advocates of crying UPL, these case law developments will likely dampen their optimism.

Big Tech and the unauthorized practice of law

If you are among the legal professionals who believe Google is performing the unauthorized practice of law and that the district courts have wrongly held that UPL restrictions thwart freedom of speech, what should we do next? Should prosecutors or bar associations prosecute Google for UPL?

If your answer is yes, then we should probably also prosecute Microsoft, which is baking LLMs into Microsoft Word and Outlook. And while we’re at it, we should probably also prosecute Meta (Facebook), whose open-source LLaMA model answers legal questions similarly. And since nearly 100 percent of the largest technology companies are laser-focused on generative AI, we should also probably do blanket UPL prosecutions of every single Big Tech company—including Amazon, since its AWS hosts LLaMa, Claude, and other LLMs.

On the other hand, if we decline to prosecute Big Tech, then do we similarly decline to prosecute smaller players? Or do we prosecute just the small players and not Big Tech? What does that “punching down” demonstrate? That states are unwilling to assert UPL statutes against the biggest players in tech for fear of losing legal battles with Big Tech’s Big Law firms, but we’re happy to try taking down smaller players?

If we truly seek to use UPL laws to prevent “consumer harm,” wouldn’t we go after the world’s largest companies — Google, Microsoft, Meta — whose wildly popular LLMs are the most likely to be used by our would-be consumer clients?

In the end, if we decline to prosecute the world’s largest companies for UPL, then that decision might well nudge us toward LLMs’ most-promising potential benefits, which involve helping bridge the access-to-justice gap.

What if bad things happen?

Of course, the purpose of UPL statutes is to protect the public. So what will happen if unscrupulous people or companies give bad advice, taking advantage of consumers? There’s a law for that! Actually, there are many laws to address unscrupulous people taking advantage of others. They include laws pertaining to:

- Negligence. “Providing this bad legal information, you failed to fulfill your duty of care.”

- Product liability. “Your legal product lacked sufficient warnings about its limitations.”

- Misrepresentation. “Your legal information and claims of being a ‘robot lawyer’ were false.”

- Unfair or deceptive trade practices. “You deceived me, saying that you were a lawyer.”

- False advertising. “Your advertisement falsely said that you were a lawyer.”

- Breach of contract. “Your terms of service said your coverage included ‘all courts,’ which was false.”

- Consumer protection laws. “This legal product failed to secure client data, resulting in consumer harm.”

- Fraud. “Your representation — that you’re a lawyer — was false, and you knew that it was false.”

- Breach of warranty. “You guaranteed a result, but you failed to deliver.”

- Probably many others. (Plaintiffs’ lawyers, get your thinking caps on!)

Over 200 years, the case law surrounding each of the common-law and statutory claims above is abundant. UPL prosecution is astonishingly rare. But laws regarding “bad people doing bad things” are bountiful.

Given the paucity of UPL caselaw, and the practical impossibility of distinguishing “legal advice” from “legal information” under the new technological regime, the common-law and statutory claims above can sufficiently protect the public from unscrupulous actors. And because the case law is more developed (millions of cases over centuries), the public is more likely to be protected.

Additionally, under each regime, who can sue? A UPL action arguably can be brought only by prosecutors or the attorney general’s office. The 10 civil claims listed above can be brought by anyone. Any member of the public who is wronged can sue; there is no need to convince a prosecutor, to wrangle a case based on the weak and minimal UPL case law, or to form a UPL working group. Civil claims democratize suing bad people doing bad things. Anyone can simply sue for negligence, fraud, product liability, or so on—without needing to even utter the term “UPL.”

Do UPL laws thwart access to justice?

At the heart of this discussion is access to justice (A2J). For years, 80 percent of consumers’ legal needs have been unmet.6 As Chief Justice Roberts has noted, today’s LLM-based tools might offer a solution. LLMs can augment the capabilities of legal aid organizations. And they can help consumers for whom paying a legal bill for even 15 minutes is impossible.

For decades, low-income and middle-income people’s de facto source of legal information has been Google. Today, their de facto source of legal information is an LLM like ChatGPT. Which is better?

If the legal profession stands on the claim that LLM-based tools are performing UPL, then it risks perpetuating the status quo. We’re failing badly. And if we do nothing, we’ll continue failing the highest goal of our profession: equal justice for all. If we instead embrace the promise of LLMs to serve broad swaths of the public that we have left unserved for decades, then perhaps we can help to bridge the massive justice gap.

Potential solutions to address the A2J gap

AI can improve access to justice. Legal Aid organizations can and should leverage LLM tools, effectively expanding their reach. If legal services transition from traditional methods to more efficient, LLM-driven approaches, they could serve more constituents—and provide even more tailored services to people who need them most. Pro se litigants can evolve from “Google-assisted” cannon fodder for lawyers into LLM-enabled parties for whom “equal justice for all” can be referenced with a straight face.

If lawyers increase their productivity with LLMs, they could expand their services by going down-market—and thereby help address that 80 percent of legal needs that are currently unmet. Economists call that an “untapped market.” Today, that low-income latent market is willing to pay what it can for reliable legal services, and with LLM-enabled efficiencies, lawyers could serve that market and make more money in the aggregate.

By embracing this potential future, lawyers could make more money, serve more people, and provide wider societal benefits.

Courts can achieve more efficient workflows

When I clerked for the Minnesota Court of Appeals, and subsequently the U.S. District Court for the District of Minnesota, I had a front-seat view of our courts’ litigation firehose. Judges and their clerks work tirelessly, but over time judicial caseloads have nonetheless become more voluminous.

What if LLMs were to help courts with that workload, allowing human judges to better serve justice? Some possible applications:

- Bench memos. What if an LLM could draft judicial clerks’ bench memos, performing in minutes what would normally take clerks all day? For each claim, summarize the parties’ positions (which may be spread over many documents): “Plaintiff argues X, defendant argues Y, the law appears to support __.” With LLMs, building that tool is trivial (I’ve already built one), and it can create a bench memo in seconds.

- Clerks for the clerkless. For those judges who lack law clerks (such as ALJs and some rural judges), the LLM-backed tools could help in more efficiently processing their caseloads.

- Substantive analyses. What if an LLM could programmatically identify weak or missing elements of claims? For example: “For the breach-of-contract claim, plaintiff lacks evidence supporting Element 3 (causation).” This is the work that human clerks do today, but slowly. If LLMs can expedite it (with no sacrifice in quality, likely even an improvement), humans will be able to more quickly identify cases’ strengths and weaknesses.

This future should consist not of machines deciding cases, but of tools aiding judges and their clerks. Just as e-discovery eased the crushing burden of millions of client documents, LLMs can help judges and their clerks sift through their hundreds of cases. These LLM-backed tools can help separate the litigants’ wheat from the chaff more quickly, enabling the human jurists (and their clerks) to more quickly exercise their human judgment.

When I clerked for Chief Judge Michael J. Davis, he would often repeat the maxim: “Justice delayed is justice denied.” LLMs can effectively expedite justice.

Conclusion: Where do we go?

The legal profession stands at a crossroads. Embracing generative AI tools such as LLMs can significantly improve legal practice and access to justice. If we’re able to assess potential concerns about free speech and guild protectionism, we might move forward with using tools to benefit the public.

The line between “legal information” and “legal advice” has always been blurry. And with LLMs, it has become virtually nonexistent. Legal tools can incorporate facts into law, providing legal information that can be indistinguishable from the work of human lawyers. But paradoxically, the technology that can do this near-magical work could also provide lawyers with additional work if corporations leverage LLM-enabled lowered costs by giving lawyers more legal work. (One example might be regulatory work that, pre-LLM, was simply too expensive to undertake.) These tools can also enable lawyers and allied professionals to serve a low-income population that has traditionally been unserved.

If lawyers, judges, prosecutors, and bar associations decline to raise the UPL alarm and instead embrace LLMs’ benefits to both the public and to the profession as encouraged by Chief Justice Roberts, our profession will continue to have ample work, while also providing improved access to justice. We can do well by doing good.

DAMIEN RIEHL is a lawyer, vLex employee, and chair of the Minnesota State Bar Association’s working group exploring the access-to-justice potential of generative AI and examining whether AI constitutes the unauthorized practice of law—but any views in this article are his own, not those of his employer, the MSBA, or the working group.

Notes

1 Minn. Stat. §481.02, subds. 1–2 (2023).

2 Georgia v. Public.Resource.org, Inc., 140 S. Ct. 1498 (2020).

3 Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., 2023 Year-End Report on the Federal Judiciary (12/31/2023), available at https://www.supremecourt.gov/publicinfo/year-end/2023year-endreport.pdf

4 Upsolve, Inc. v. James, Case No. 1:22-cv-00627-PAC (S.D.N.Y. 5/24/2022), available at https://www.docketalarm.com/cases/New_York_Southern_District_Court/1--22-cv-00627/Upsolve_Inc._et_al_v._James/68/, appealed to Case No. 22-1345 (2d Cir.), available at https://www.docketalarm.com/cases/US_Court_of_Appeals_Second_Circuit/22-1345/Upsolve_Inc._v._James/

5 Nutt v. Ritter, Case No. 7:21-cv-00106 (E.D.N.C. 12/20/2023), available at https://www.docketalarm.com/cases/North_Carolina_Eastern_District_Court/7--21-cv-00106/Nutt_v._Ritter_et_al/63/

6 Legal Services Corporation, The Unmet Need for Legal Aid, available at https://www.lsc.gov/about-lsc/what-legal-aid/unmet-need-legal-aid